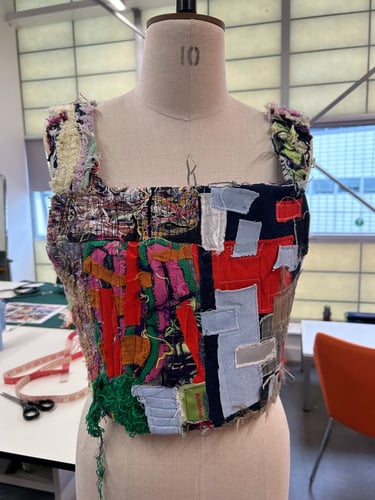

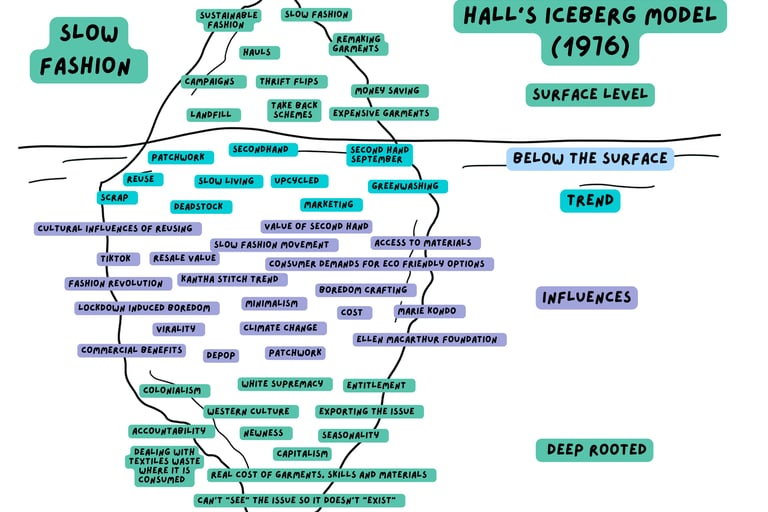

Slow Fashion Made Slowly - Support Your Local Spice Girl - remaking with textiles waste

masters research:

How can I upscale my slow fashion brand while utilising textile waste and offcut fibres, taking inspiration from my heritage and ancient Culture of upcycling, reusing, and remaking?

Project Question

How can I upscale my slow fashion brand while utilising textile waste and offcut fibres, taking inspiration from my heritage and ancient Culture of upcycling, reusing, and remaking?

The project seeks to reduce textile waste and scrap material while considering methods for scaling the small fashion business. Since launching my brand, I've received queries about stocking my designs from buyers from well-known brands both domestically and globally. I've struggled to duplicate reused things in the quantities buyers require, limiting my growth as a small business. Another aim is to develop an alternative option that opposes textile waste disposal exports to the Global South to dismantle colonialism. The surplus waste disposal of the Global North has disproportionately overburdened and harmed countries in the Global South (Dead White Man's Clothes, 2016).

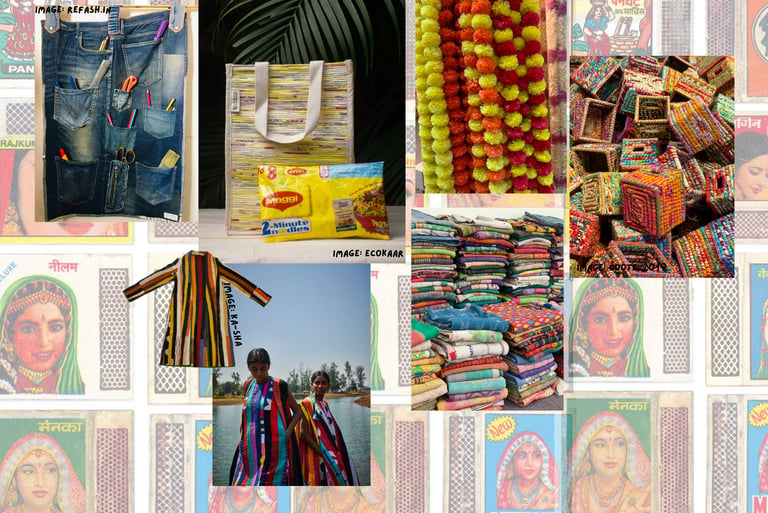

In pursuing sustainability, Indian society upholds the ethos of "Jugaad," a symbol of resourceful innovation and recycling, as elucidated by Tsur in 2017. This research embarks on a cross-cultural journey rooted in historical contexts, embracing ancient upcycling traditions from Indian communities and global diasporas, as expounded by ASSOMULL in 2021. Aligned with the multidisciplinary field of discard studies, as illuminated by Liboiron and Lepawsky in 2022, it delves into waste disposal from cultural, social, environmental, economic, and political angles. The primary objective is to extract insights from diverse cultural backgrounds through upcycling, recycling, and recreation practices to enhance our understanding of scalability within the "slow fashion" movement.

The practice-based MA project underscores the transformative power of storytelling in reshaping attitudes towards textile waste, aiming to amplify the scalability of sustainable fashion practices infused with Jugaad's cultural and historical elements.

The results chapters reveal workshop participants' insights into matriarchal influences on sustainable living, differing reuse practices across cultures, and the cultural backdrop shaping recycling and repurposing practices. The research also unveils scalability challenges sustainably, emphasising collaboration among stakeholders and technological advancements for a more sustainable industry amid complex supply chains and material sourcing. The fashion and textile waste arena poses challenges and opportunities, encouraging transformative change.

20% of worldwide waste is created by the textiles & Fashion industry

1% or less of textile waste is recycled

40m tonnes of waste created by the fashion industry each year

99% of leading fashion brands do not reveal if garment workers are paid living wages

29% of UK consumers have bought second-hand fashion items in the last 12 months.

A 321% year-on-year jump in searches for ‘upcycled jeans’.

Exponential demand increase: A 117% year-on-year increase in demand for upcycled, recycled, repurposed and reworked items.

(Bell, 2022)

Jugaad is an Indian societal and cultural approach to problem-solving with limited resources, essentially doing more with less (Radjou, Ahuja and Prabhu, 2012).

Indian “Jugaad” TEXTILES AND FASHION influences

Jugaad is derived from the Hindi words "jog" and "jod," which means "to add" (Tewari, 2016).

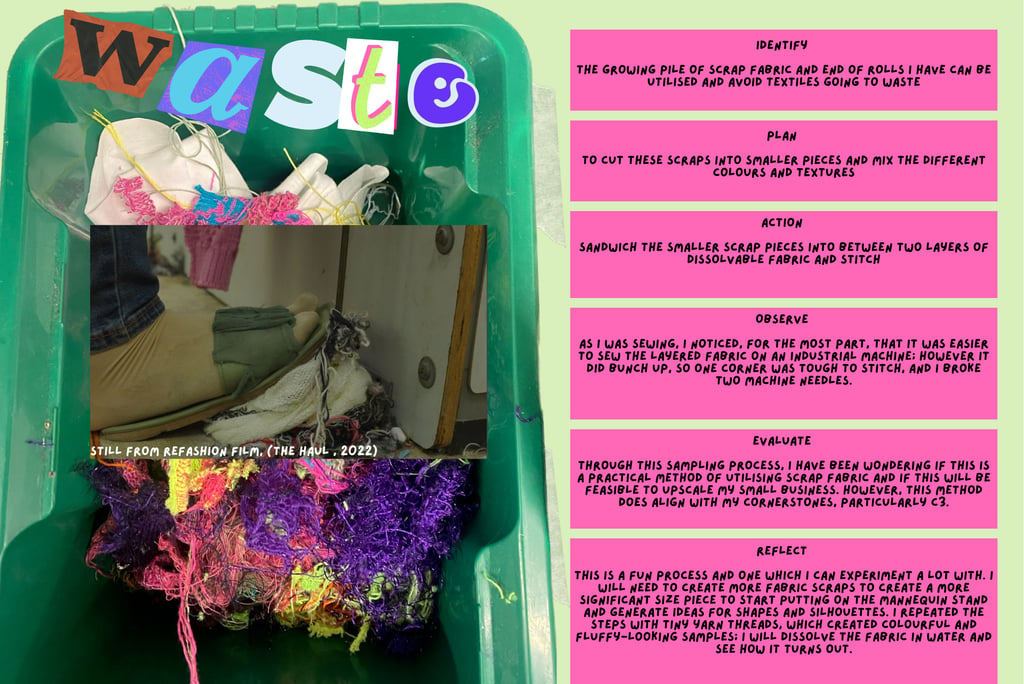

Action research: reflective practice

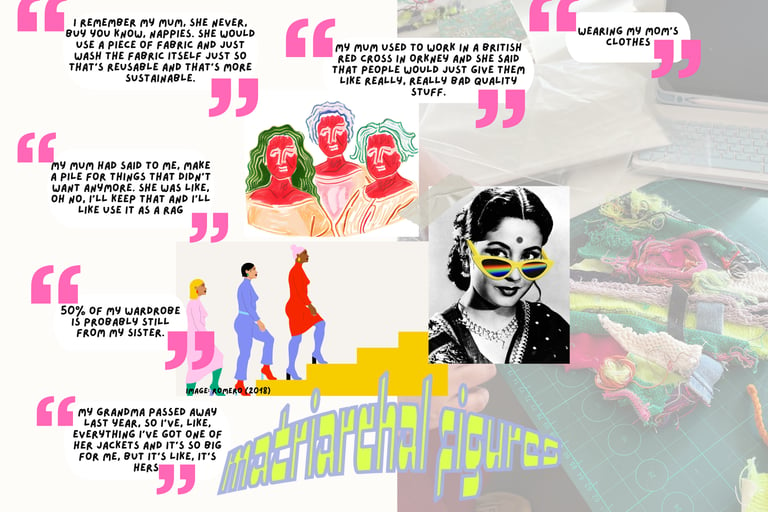

Female participants at the workshop shared anecdotes about sustainable living practices, often attributing their approach to matriarchal influences within their families. These influential figures were pivotal in introducing and endorsing purposeful consumption habits.

Parents and older people significant influence on moulding their children's sustainable behaviours and consumption habits.

Participants identified obstacles in attaining a 'unified appearance' and aligning with the brand's visual identity.

Some questioned increasing production and giving factories access to materials for scalability, while others noted the paradox of demanding leftover fabric that shouldn't exist in the first place.

Matriarchal figures

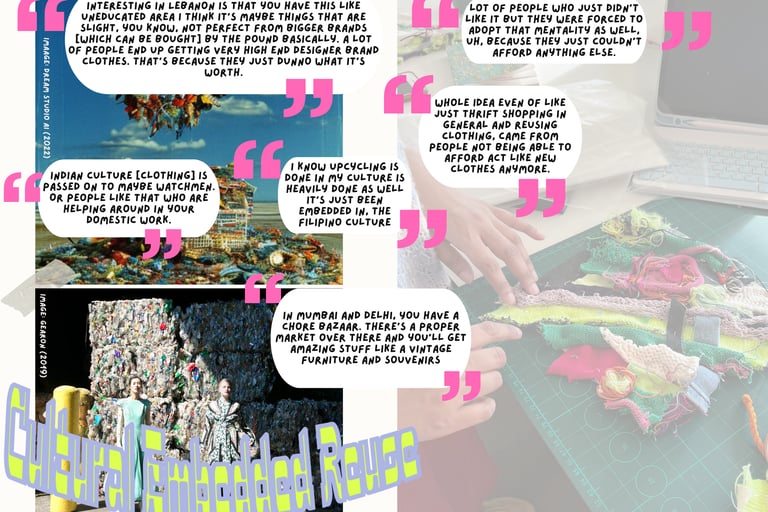

Cultural Embedded Reuse

waste scalability

Those with origins or cultural ties to emerging market countries shared a wide range of personal tales, particularly concerning their upbringing and participation in practices such as recycling, repurposing, and prolonging the utility of items.

When discussing the significance of upcycling practices, participants stated that 'upcycling is embedded' in their cultures and stems from being 'forced to adopt the mentality' due to financial restrictions that left them with no other options.

Suppose an organisation’s entire operational framework is based on utilising wasted resources. In that case, it should remember that its commercial identity, aesthetic, or brand image may change depending on the type of waste it can receive.

Other cultures have adapted to living more sustainably out of necessity or instability. Participants had a sense of pride in their work and high satisfaction with the results.

It seems intuitive for participants to document their creations, showcasing contentment and attaching emotional significance to the samples created in the workshop.

In the Global North, people tend to romanticise second-hand garment shopping, finding it rewarding to purchase clothing second-hand. Providing consumers with a positive feeling will enable them to make better purchases. Nations that receive exported second-hand apparel appreciate the value of repurposing and remanufacturing such items, yet they often lack adequate options for consumers to purchase second-hand products. Typically, the trade of second-hand goods occurs between businesses rather than directly from businesses to consumers.

Developing and emerging countries often donate clothes to housekeepers or security employees. While these countries have secondhand or thrift retail stores, the concept is newer in some areas, with less variety in Thailand and India. Individuals often feel guilty while discarding unwanted clothing, encouraging them to continue wearing the garments until they are unfit for use. Some individuals donate these items to charities, but such organisations often cannot resell the donated garments due to their poor condition. As a result, such donations are frequently exported for textile waste recycling, leading to landfilling or incineration. This thinking eventually prolongs the disposal process, wasting critical time and money.